The Conjoint Toolbox -How Data-Driven Decision Design Puts Industry Leaders Ahead of the Pack

Most of us like to believe that the products we choose—our phones, cars, subscription services—are a reflection of personal preference. We imagine that companies put options out into the world, and consumers vote with their wallets. The best products win; the worst fail.

But beneath that comforting story lies a far more calculated reality. The choices we face—the features we’re offered, the bundles we can’t quite refuse, and the prices we reluctantly pay—are not random. They are the result of a research technique that has quietly shaped modern marketing for decades: conjoint analysis.

Rarely discussed outside of market research circles, conjoint analysis has become an essential tool for companies designing products and setting prices. It works by forcing consumers to make trade-offs, revealing not what people say they value but what they will actually pay for. Behind countless product launches and pricing strategies lies a trove of data modeling, run long before we ever see a price tag.

The Origins of a Quiet Revolution

Conjoint analysis emerged in the 1970s, born from a simple but powerful insight: asking people directly what they want is a bad way to understand them. When surveyed, consumers often overstate their willingness to pay, inflate the importance of features that make them look rational, and ignore trade-offs entirely.

The method quickly found its first big commercial applications in the airline industry of the late 1970s and early 1980s. As deregulation reshaped U.S. air travel, carriers like American Airlines and United Airlines were desperate to understand how much passengers valued things like flexible tickets, in-flight meals, or direct routes. Conjoint analysis revealed that many travelers would pay less for restricted fares if it meant cheaper flights. This insight helped lay the groundwork for modern fare classes—super-saver tickets for price-sensitive travelers, flexible fares for business travelers—all designed to maximize revenue without alienating customers.

A Case Study: The Ford Taurus

Perhaps the most famous early success story came from the auto industry. In the early 1980s, Ford was in trouble. Japanese imports—reliable, fuel-efficient, and competitively priced—were steadily eroding its U.S. market share. The company’s lineup felt dated, its design language uninspired, and its production costs too high for aggressive pricing. Internally, there was recognition that incremental updates would not be enough; Ford needed a car that could not only compete but signal a dramatic change in the company’s direction.

Enter the Ford Taurus, a project that from the outset was positioned as a make-or-break bet. Ford’s leadership realized that the usual process—relying on the instincts of designers and product planners—would be risky in a market reshaped by new competitors and changing consumer expectations. They turned instead to conjoint analysis, a relatively new but powerful tool for understanding customer trade-offs.

The research team didn’t simply ask drivers what they wanted in a car; they presented structured scenarios that forced respondents to choose between bundles of features and price points. Should the car offer more horsepower at the expense of fuel efficiency, or slightly less power with better mileage? Would customers pay more for a roomier interior, or would they trade that space for sleeker styling? What trim levels, materials, and technology features would tip the balance between “maybe” and “buy”?

By systematically analyzing these trade-offs, Ford was able to identify the sweet spots—configurations that delivered the greatest perceived value to the largest number of target buyers. The data revealed that while fuel economy was important in the post–oil crisis market, many consumers still valued performance and comfort, provided the price felt justified. Styling, too, emerged as a differentiator: buyers were drawn to a modern, aerodynamic silhouette that stood apart from the boxy sedans then dominating the road.

Armed with these insights, Ford’s design and engineering teams crafted a car that felt as though it had been built “from the customer backward.” The Taurus offered a blend of performance, efficiency, spaciousness, and design sophistication at a price point calibrated to its perceived value. Importantly, the final product did not feel like a market-research experiment—it felt cohesive, aspirational, and authentically Ford.

Launched in 1985, the Taurus was an immediate hit. It not only outsold its domestic rivals but began to reclaim share from Japanese automakers. By 1992, it was the best-selling car in America, a position it held for five consecutive years. Beyond its commercial success, the Taurus became a cultural touchstone of 1980s America—sleek, modern, and a symbol of U.S. manufacturing revival.

The Taurus project remains a landmark example of how rigorous consumer modeling, when embedded early in the design process, can transform a struggling product line into a blockbuster. It demonstrated to the wider business world that conjoint analysis could do more than fine-tune pricing or feature sets—it could redefine a company’s competitive trajectory.

How Procter & Gamble Transformed Everyday Goods

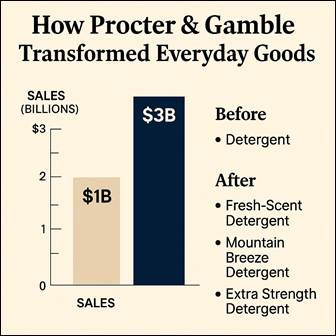

At the same time, consumer packaged goods companies were quietly discovering that conjoint analysis could be just as powerful for products far removed from the glamour of automobiles. Procter & Gamble, already a titan of household brands, began experimenting with the technique in the 1980s to guide the development of product line extensions.

The competitive landscape had shifted. Private-label brands were gaining traction, offering lower prices on staples like detergents, shampoos, and cleaning products. For P&G, which relied on both scale and brand loyalty, the challenge was to defend market share without engaging in a race to the bottom on price. The company needed to know, with precision, which attributes truly drove purchase decisions—and which were merely cosmetic.

Conjoint analysis offered exactly that clarity. Instead of relying on focus groups or direct surveys, P&G presented consumers with structured trade-offs, forcing them to choose between different combinations of fragrance, packaging size, cleaning power, and price. The data revealed surprising truths. Shoppers would readily pay a premium for detergents with added scent boosters, associating fragrance with freshness and performance. Packaging color, however, had almost no measurable impact on choice.

These findings reshaped P&G’s product strategy. The company rolled out a wave of targeted variations—“fresh scent,” “mountain breeze,” “extra strength”—each calibrated to appeal to a specific segment and each priced according to its modeled value. Store shelves began to fill with what appeared to be a bounty of consumer choice, but behind that variety was a disciplined, data-driven system designed to capture every incremental dollar of willingness to pay.

The approach proved so effective that it altered the way consumer goods companies thought about line extensions. What looked like abundance was, in fact, a portfolio engineered through meticulous modeling, ensuring that nearly every shopper found something that felt tailored to them—while maximizing revenue for the brand.

How It Works Today

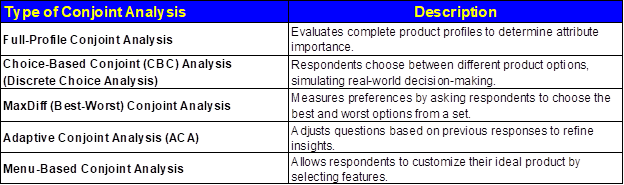

Modern conjoint analysis has grown both more sophisticated and more personalized. Adaptive choice-based conjoint (ACBC) allows respondents to “build their own” product before answering tailored choice questions, while menu-based conjoint (MBC) models decisions for customizable offerings like meal plans, software subscriptions, or telecom bundles.

Advanced statistical techniques—most notably Hierarchical Bayes estimation —allow researchers to derive individual-level insights even with limited data from each respondent. These utilities feed into market simulators —digital crystal balls that let companies test “what-if” scenarios before spending millions on production or marketing.

· What if we raised the price by 10 percent?

· Would customers choose a cheaper rival if we removed a feature?

· How would launching a new version affect the sales of our existing models?

Conjoint analysis answers these questions with startling precision.

The Companies That Master It

The most sophisticated players in technology, retail, and consumer goods have made conjoint analysis a core strategic capability.

Amazon relentlessly tests Prime’s pricing and shipping configurations to learn not only what drives adoption, but also what customers will tolerate before defecting. Apple has turned iPhone storage upgrades into a masterclass in value extraction, pricing each tier with uncanny accuracy to match what customers are willing to pay. Tesla continually adjusts trim levels and option packages to maximize revenue while maintaining the brand’s aspirational appeal.

These companies are not guessing. They are running simulations—mapping consumer preferences mathematically, stress-testing scenarios long before a product reaches the market.

The Ethics of Willingness-to-Pay Exploitation

With this power comes a question many executives prefer not to confront: how far should a company go in monetizing consumer preferences?

When airlines learned through conjoint analysis that flexibility was less important to many passengers than assumed, they didn’t lower prices universally. Instead, they introduced cheaper, inflexible fares and increased the price of flexible tickets. The result was a segmented system designed to extract maximum value from each traveler—profitable, but less egalitarian.

The same logic now governs industries from software to quick-service dining. Conjoint is not only used to understand what customers want, but to pinpoint the exact price at which they will say yes—and then capture it. Critics call this behavioral exploitation, arguing that such precision edges into manipulation. Defenders see market efficiency, where better data aligns prices more closely to perceived value. In practice, the boundary between the two is anything but clear. When every price point is optimized for extraction, consumers may end up paying more without feeling they have meaningful alternatives.

The Uneasy Truth

Conjoint analysis almost never makes the news, but it quietly decides much of what you see, choose, and pay for. Its fingerprints are all over daily life. That “three-tier” streaming plan isn’t random—it’s engineered to funnel you toward the middle option, the one with the fattest profit margin but still wrapped in the illusion of being a sensible compromise.

Airlines play the same game. The whiplash contrast between a cramped economy seat and a wide, reclining business-class pod isn’t an accident—it’s design. The discomfort is intentional, just enough to make you consider paying more. Even the way Wi-Fi, seat selection, and checked bags are bundled—or stripped out—is the product of conjoint modeling that tests exactly which perks can be monetized without triggering revolt.

Your phone is priced the same way. The gap between the base model and the “Pro” version with a marginally better camera or slightly larger display isn’t guesswork. Companies know, down to the percentage point, how many of us will stretch for the upgrade and how many will settle for less. These are not neutral reflections of demand—they are carefully constructed revenue traps.

We like to think our purchases are personal choices. In reality, the “freedom” we feel is often pre-scripted. The trade-offs we face have already been simulated thousands of times, with every variable fine-tuned to push us toward the outcome that best serves the seller. By the time you spring for premium shipping or that high-storage phone, your “decision” has already been predicted, priced, and packaged.

Conjoint’s quiet dominance reveals the uncomfortable truth about modern commerce: it no longer just responds to demand—it manufactures it. The products, the prices, the very perception of choice itself are increasingly the product of invisible algorithms built not to please you, but to profit from you.